AYAHUASCA: THE HISTORY OF THE SPIRIT MEDICINE

AYAHUASCA: THE HISTORY OF THE SPIRIT MEDICINE

Scott Emerson, MD, ABIHM, FACMT

Integrative Medicine Physician & Medical Toxicologist

Timeless Healing

Shamanism and the Historic Perspective on Healing

Shamanism is the world’s oldest profession and shamans are the world’s oldest professionals. Shamanism is defined as the practice of healing and divination that involves the purposeful induction of an altered state of consciousness called the “shamanic journey”, in which the shaman enters into “non-ordinary reality” and seeks knowledge and healing power from spirit beings existing in those alternate worlds. In arctic regions, altered states are mainly induced by sensory deprivation, drumming, fire, and rhythmic rattling, while in temperate and tropical regions psychotropic mushrooms and plants also are used.

There is good evidence that remarkably similar shamanic practices of healing independently evolved among the peoples of all habitable continents on earth far greater than ten thousand years ago. However, the rise of the scientific method (Newton, Galileo, Descartes) and it’s conflict with the Christian Church in the 1600s in Europe, caused a rift in the practice of medicine between shamanism and science in western cultures which has grown progressively wider into modern times. The natural world was detached from spirituality, and anything to do with material objects and measurable forces was in the science domain. Conversely, anything with purpose, value, morality, subjectivity, psyche, or spirit, was in the religious domain and science and doctors stayed out of it.

Shamans are well skilled in the diagnosis of spirit disorders and the pharmacopeia of “plant allies”. Their perspective is that of totally integrated systems rather than fragmented separate systems, and the belief that most illness enters from within not from without. For them, the first job is to augment the personal power and energetic field integration of the sick patient, then, counter act the power of the illness producing agent, rather than vice versa as in traditional Western Medicine.

Specifically, the shamanic healers in the Amazon that I have worked with note that the vibrational, spirit effects, and intent of use of plants is equal if not more important for maximum effect than biochemistry. The plant spirits are “seeing” through the shaman’s senses just as the shaman is “seeing” through them, in a symbiotic bridging or vectoring phenomenon.

“Because plants are both male and female at the same time they “vector” to both sexes equally, bringing us a separate reality so that we can understand this one in the best way. They are here as our friends and teachers, sometimes gentle, sometimes strict. We ask the plants, What happens here? How can we help you, and you me? We ask the plant what the shadow of things are, particularly to help us to humbly know and find our own shadow and the patient’s shadow. To know your own shadow is like a permanent celebration, a guide to the righteous spiritual path. “Seeing” may be different for each shaman. It can be like a feeling in your own body like an empath, but it is most important to avoid ego contamination and be a clear vessel so that you are not projecting onto the patient. You must always be thankful and grateful to helper plants and for deeper states of being.” – don Theo Paredes, PhD

What is Ayahuasca?

The name ayahuasca is from the South American Indian language, Quechua, meaning literally, aya – souls, huasca – vine, or “vine of the souls”. It is a tea made from boiling two different parts of two different jungle plants; the woody stems and bark of Banisteriopis caapi, a large liana or vine, and the leaves of Psychotria viridis, a bushy plant growing in the jungle under story.

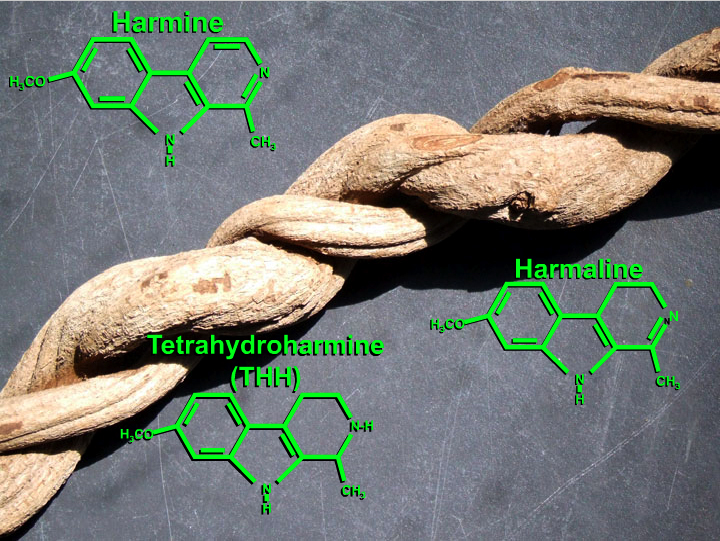

The bark of B caapi contains the beta carbolines (actually three ringed, cyclized, tryptamines) harmine, tetrahydroharmine, and harmaline, possessing powerful, reversible, extracellular & intracellular monoamine oxidase subtype A inhibitor (MAOI) activity and weak serotonin reuptake inhibition activity. These harmala alkaloids also act as antimicrobials, anti-helminthics and vasodilators.

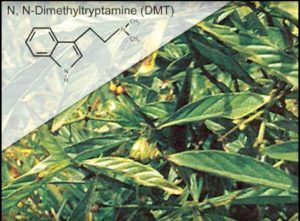

P viridis leaves (especially the double veined forms) contain N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT), a powerful, but orally inactive, psychedelic. It should be noted that DMT is also naturally present in humans as an endogenous “hallucinogen” with a growing list of beneficial effects. However, it’s role in normal physiology is still only partially understood. When released in small amounts by the pineal gland and other areas of the brain, DMT likely plays a natural, enabling role in dreaming and some mystical states of consciousness. Some feel that DMT is more of an entheogen – to touch within, than a hallucinogen.

DMT triggers a unique simultaneous activation of serotonin subtype 2A receptors as well as metabotropic glutamate (mGlu2) receptors in neuron cell membranes. This unique action at the serotonin receptor makes it the “ultimate psychedelic”. Further, and most interestingly, serotonin producing neurons prefer to store and use DMT over their “normal” serotonin neurotransmitter. The evolutionary meaning of this remains uncertain. The body appears to also create large amounts of DMT in response to low oxygen levels or low blood flow states that would occur at the time of birth, near death, or in blood loss shock. In these adverse situations, DMT is likely acting to protect all cells, especially brain nerve cells, from damage. In this instance, this fascinating substance is working at a different site deep within each cell at the Sigma-1R receptor to optimize mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum organelle function, and improve the efficiency, protein structure, robustness, and longevity of normal cells.

Other components of the ayahuasca tea include a multitude of antioxidant polyphenols acting as immune modulators and anti-inflammatory agents. Ayahuasca is an emetic as well as a purgative, most likely the result of both a central and peripheral serontonergic effect. It is traditionally used in nocturnal ceremonies throughout the western Amazon basin by indigenous peoples for healing, prophecy, divination, and sorcery. The tea causes hours of brilliantly colored visions and auditory hallucinations, and “frees the soul from corporeal confinement, allowing it to wander free and return to the body at will, to travel to infinite realms and communicate with ancestors (human, animal, and plant)”. The purging is viewed as an important part of ayahuasca’s cleansing of the patient.

Depending on the tribe or region, there are many different names for ayahuasca, including “cappi”, “dapa”, “kahi”, “natema”, “pinde”, and “yaje”. According to the natives, different individual vines of the species B caapi have their own “personalities” and cause dramatically different effects and can be used for specific different purposes and healings. In addition, occasionally Nicotinia sp. (nicotine), Brugmansia sp. & Brunfelsia sp. (scopolamine, atropine) are added to ayahuasca by shamans for specific medical, or prophesy purposes which may need to be addressed.

Ayahuasca: Pre History

The exact origins and use of ayahuasca in the Amazon basin currently remain lost in the mists of pre history, unless some artifact is uncovered that would unequivocally establish the antiquity of its usage. The fact that the practice, culture, and use of ayahuasca was already widespread over a vast geographic region when it came to the attention of Western ethnographers in the mid 1800s, argues for its antiquity. There is abundant archeological evidence in the form of pottery, anthropomorphic figurines, snuffing trays, and pipes, that indicate that plant hallucinogenic snuff use (Andenanthera sp.), was well established in the region over 4000 years ago. It is now also thought that a very advanced and sophisticated civilization existed in the Andes of Peru as early as 2200 BC, much earlier than was believed (celestial observatory find, May 2006), heightening interest and search for evidence of cultural and shamanic practices of this time. The odds against the “discovery” or invention of ayahuasca must have been astronomical, since it is prepared from the unlikely combination of two different jungle plants out of hundreds of thousands, if not millions of possibilities. Further, since neither of these plants is psychoactive alone when ingested, the mystery and odds against “discovery is deepened. The mestizo ayahuasqueros in Peru when asked about this “discovery”, state that the knowledge came from dreams and communion directly with “lower plant allies and teachers” who showed our ancestors the way to knowledge of the great teacher, ayahuasca.

Ayahuasca: The 19th Century

In 1851, the English botanist, Richard Spruce, encountered the use of an intoxicating beverage among the Tukano Indians of the Rio Uapes in Brazil. He collected flowering specimens from the large jungle liana used as the source of the beverage, named it Banisteropsis caapi, and collected voucher specimens for later chemical analysis. In 1858, Spruce documented use of the same plant by the Guahibo Indians on the upper Rio Orinoco of Columbia and Venezuela, then several months later found the Zaparo Indians of Andean Peru taking a narcotic beverage prepared from the same plant that they called ayahuasca. That same year, Ecuadorian geographer, Manuel Villavicencio, published the first written report of the use of ayahuasca in sorcery and divination on the upper Rio Napo, describing his own self-intoxication, but describing no botanical details. Throughout the late 1800s various explorers continued to report on encounters with various widespread Amazon tribes use of an intoxicating tea. About the same time as Spruce’s initial encounter with ayahuasca, a seemingly detached, but essential piece of the ayahuasca puzzle was discovered when German chemists Gobel and Fritsch isolated the beta carbolines, harmine and harmaline from Syrian rue, Peganum harmala, a desert plant from half a world away in central Asia.

In 1851, the English botanist, Richard Spruce, encountered the use of an intoxicating beverage among the Tukano Indians of the Rio Uapes in Brazil. He collected flowering specimens from the large jungle liana used as the source of the beverage, named it Banisteropsis caapi, and collected voucher specimens for later chemical analysis. In 1858, Spruce documented use of the same plant by the Guahibo Indians on the upper Rio Orinoco of Columbia and Venezuela, then several months later found the Zaparo Indians of Andean Peru taking a narcotic beverage prepared from the same plant that they called ayahuasca. That same year, Ecuadorian geographer, Manuel Villavicencio, published the first written report of the use of ayahuasca in sorcery and divination on the upper Rio Napo, describing his own self-intoxication, but describing no botanical details. Throughout the late 1800s various explorers continued to report on encounters with various widespread Amazon tribes use of an intoxicating tea. About the same time as Spruce’s initial encounter with ayahuasca, a seemingly detached, but essential piece of the ayahuasca puzzle was discovered when German chemists Gobel and Fritsch isolated the beta carbolines, harmine and harmaline from Syrian rue, Peganum harmala, a desert plant from half a world away in central Asia.

Ayahuasca: The Early 20th Century (1900 – 1950)

During this period, the first serious chemical investigations of the active principals of ayahuasca were conducted. Confusion reigned initially because of simultaneous investigations by several independent groups of investigators. But as these investigations were eventually published in the scientific literature clarity began to emerge. Between 1905 and 1925 various harmala alkaloids were identified unfortunately from multiple investigative fronts, and they were thus given various names such as telepathine, yageine, and banisterine. The lack of botanical voucher specimens, confusion of the proper plant source for the ayahuasca beverage due to an early misreading of Spruce’s field notes (this error propagated itself through the scientific literature for 4 decades!), and impurity of the isolated alkaloids, made this work of dubious value. However, in 1928, Lewin and Elger working from vouchered botanical specimens, isolated pure “harmine” from B caapi which was found in Syrian rue 80 years prior, and further found it identical to the previously described “banisterine” from B caapi. That same year, Beringer conducted the first human study using “banisterine”(harmine) in 15 post encephalitic patients with Parkinson’s disease with dramatic reversal of symptoms. The identical nature of “banisterine and “harmine” was reconfirmed in 1939 by Chen and Chen and the name harmine was chosen for the alkaloid.

Ayahuasca: Mid 20th Century (1950 – 1980)

During these three decades both botanical and chemical studies continued apace, and new discoveries laid the groundwork for an eventual explanation of the unique pharmacologic action of ayahuasca. In 1957, Hochstein and Paradies confirmed the active alkaloids of B. caapi were harmine, tetrahydroharmine, and harmaline. In 1958, Udenfriend et al. working at the NIH Laboratory of Clinical Pharmacology, demonstrated that the beta carbolines like harmine were potent, reversible, inhibitors of the enzyme monoamine oxidase. In 1960, the famed ethno botanist Richard Evan Schultes, wrote the first detailed reports from 20 years of field work in the Amazon. Concerning ayahuasca, he noted that an admixture plant Psychotria viridis was always added to the brew to strengthen and extend the visions.

The late 1960s arrived and a unique symposium was organized by the US Department of Health Education and Welfare. It was held in San Francisco in 1967 during the “summer of love” and titled “Ethnopharmocologic Search for Psychoactive Drugs”. Participants included the young Cannabis researcher, Andrew Weil, MD, Richard Evan Schultes, PhD, chemist Alexander Shulgin, PhD, and toxicologist Bo Holmstedt of the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, Sweden. This was the first time that a conference on the botany, chemistry, and pharmacology of psychedelics had been held, and as it turned out, it was certainly the last time such a conference would be held under government sponsorship. An interesting commentary of the time though, on how little was understood concerning the pharmacology of oral tryptamines and their activation by MAOIs, is, that despite every attempt to be comprehensive concerning ayahuasca, the mechanism of it’s psycho activity was still thought to be solely MAO inhibition. The next year (1968) Der Marderosian et al. reported that the alkaloid fractions obtained from P. viridis were the potent, short acting, (but orally inactive) hallucinogen, N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT). Although DMT had been known as a synthetic since 1931 (Manske), it’s hallucinogenic properties solely as a parenteral drug had not been discovered until 1957 (Szara). In 1969, Pinkley, Der Marderosian, and Schultes published their initial findings on the DMT containing admixture plant P viridis, theorizing that DMT, orally activated by beta carbolines in B caapi was responsible for much of the psychotropic activity of the ayahuasca tea.

Ayahuasca: Late 20th Century (1980 – present)

Sixteen years later in 1984, Dennis and Terence McKenna, et al., experimentally confirmed the aforementioned theory using vouchered botanical specimens, and samples of ayahuasca teas used by mestizo ayahuasqueros in Peru. They also studied rat liver MAO systems showing that the brews were extremely potent MAO inhibitors, even when diluted by many orders of magnitude. In 1986, Luna, McKenna and Towers again working with ayahuasqueros in the Peruvian Amazon, published in 1995, the first comprehensive tabulation of species used as admixture plants to the basic ayahuasca tea as well as the biodynamic constituents contained in each of them. This work represents an extensive and unexplored frontier of folk pharmacopoeia worthy of investigation for new therapeutic agents. Many of the frequent ayahuasca users were also found to have superior physical health even at advanced ages. In 1987, the Uniao do Vegetal (UDV) meaning “the union of plants” a Brazilian based religion combining indigenous beliefs and Christian teachings using ayahuasca routinely as a sacrament, successfully petitioned the Brazilian government to remove ayahuasca from the list of banned “drugs”. The Brazilian government declared ayahuasca to be a legal substance when used within the context of religious practice. Brazil became the first nation in 1600 years to allow the use of plant hallucinogens for spiritual purposes by its non-indigenous inhabitants. This decision however was subject to provisional review. In 1991, the UDV invited the international scientific community to conduct studies on the health of any of their thousands of members. The UDV Church in advance of the provisional review, wanted objective scientific proof that their “hoasca tea” was safe, and did not cause addiction or other adverse reactions. In 1995 the Hoasca Project was launched. Medical researchers from Europe, the United States, and Brazil studied the oldest and largest UDV congregations in Brazil, resulting in one of the most carefully controlled and conducted, comprehensive, multifaceted, investigations of the chemistry, physiology, kinetics, psychological effects, and psychopharmacology of a psychedelic drug ever to be carried out in the 20th century. Between 1994 and 1999 Grob, Callaway, McKenna et al. published a series of peer reviewed scientific papers on the Hoasca Project. The key findings:

- UDV members commonly underwent experiences that changed their lives and behavior in profound ways, including discontinuing cigarette, alcohol, and recreational drug use.

- UDV members had healthier personality measures on neuropsychiatric testing and superior scores on measures of concentration and short-term memory than matched controls.

- UDV members showed persistent elevation in serotonin uptake receptors in platelets, possibly explaining some of the above mentioned long term adaptive mental changes, if changes in the CNS serotonin receptors are paralleling those found in the platelets.

- The regular use of the “hoasca tea” within the supportive context of the UDV, is safe and without any long term toxicity, and further, apparently has lasting positive influences on physical and mental health.

The congregations of the ayahuasca-based churches like the UDV are growing and rapidly spreading worldwide out of their site of origin in the Amazon. In February 2006, the Supreme  Court of the United States gave a green light to the UDV Churches in the USA when they ruled that they can use the illegal drug, DMT, in the ayahuasca tea in worship services, and “that the practice is protected by the 1993 Religious Freedom Restoration Act”.

Court of the United States gave a green light to the UDV Churches in the USA when they ruled that they can use the illegal drug, DMT, in the ayahuasca tea in worship services, and “that the practice is protected by the 1993 Religious Freedom Restoration Act”.

There is now great interest in ayahuasca and its component compounds as therapies for a wide-ranging list of common diseases of civilization. These include, PTSD, substance abuse, cancer, cardiomyopathy, retinal dysfunction, perinatal and traumatic brain injury, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, HIV-related dementia, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and major depression.

Ayahausca: Musings

The shaman ayahuasqueros of the Amazon say that the plants call, and that those who will listen and look receive great teachings and insight from these powerful elders and symbiotic allies of the Earth’s biosphere. And, that these are indeed, great avatars from the Kingdom of Plants who are calling.

Without question, something very improbable and mysterious occurred thousands of years ago, for those humans who were able to humble themselves before the incredible scope and vastness of the plants living in the Amazon basin. The spirit medicine, ayahuasca, revealed itself to us as a way to heal our egocentric reason and consumption by consulting the ecstatic, mystical, and profound wisdom of the ancient keepers of our planet.

References in Chronologic Sequence

Achterberg, J, “Imagery in Healing”: Shamanism and Modern Healing, Boston and London, Shambhala, (1985)

Metzner, R, “Sacred Vine of Spirits: Ayahausca”, Amazon Vine of Visions, Park Street Press, Rochester, Vermont, pg 1-39 (2006)

Callaway, J, “Sacred Vine of Spirits: Ayahuasca”, Phytochemistry and the Neuropharmacology of Ayahuasca, Park Street Press, Rochester Vermont pg 94-116 (2006)

Freska E, Bokor P, Winkelman M, “The Therapeutic Potentials of Ayahuasca: Possible Effects against Various Diseases of Civilization”. Frontiers in Pharmacology 7: 35 (2016)

Szabo, A, et.al.: “The Endogenous Hallucinogen and Trace Amine N,N-Dimethyltryptamine (DMT) Displays Potent Protective Effects Against Hypoxia via Sigma-1 Receptor Activation in Human Primary iPSC-Derived Cortical Neurons and Microglia-Like Immune Cells” Front Neurosci., pg 1-23 (14 Sept, 2016)

Carbonaro,T, Gatch, M: “Neuropharmacology of N,N-dimethyltryptamine” Brain Research Bulletin, (2016)

McKenna, D, “Sacred Vine of Spirits”, Ayahuasca: An Ethnopharmacologic History, Park street Press, Rochester, Vermont, pg 40-62 (2006)

Caskie, S, International Editor, The Week, “ A South American Stonehenge”, pg 22, June 2, (2006)

Spruce, RA, “On Some Remarkable Narcotics of the Amazon Valley and Orinoco. Ocean Highways.” Geographical Magazine 1: 184-193 (1873)

Villavicencio, M “Geografia de la Republica del Ecuador”, New York, Craighead (1858)

Lewin, L “Sur une Substance Envirante, la Banisterine, Extraite de Banisteria caapi Spr. Comptes Rendeus 186: 469ff (1928)

Beringer, K “Ube rein neues, auf das extrapyramidal-motorische system wirkendes Alkaloid (Banisterin)” Nervenarzt 1:265-275 (1928)

Chen, AL, and Chen, KK, “Harmine: The Alkaloid of caapi.” Quarterly Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 12: 30-38 (1939)

Hochstein, FA and Paradies, AM, “Alkaloids of B caapi and Prestonia amazonica.” J of American Chemical Society 79: 573ff (1957)

Udenfriend, SB, et al, ”Studies with Reversible Inhibitors of Monoamine Oxidase: Harmaline and Related Compounds” Biochemical Pharmacology 1: 160-165 (1958)

Schultes, RE and Raffauf, R, “Prestonia: An Amazonian Narcotic or Not?” Botanical Museum Leaflets, Harvard University 19: 109-122 (1960)

Schultes, RE, “The place of ethnobotany in the ethnopharmacologic search for psychoactive drugs.” In Ethnopharmacologic Search for Psychoactive Drugs, ed. Efron, DH, Holmstedt, B, Kline, NS. US Public Health Service Publication No. 1645. Washington, DC. : GPO (1967)

Der Marderosian AH, Pinkley HV, Dobbins MF, “Native use and Occurrence of N,N-dimethyltryptamine in P viridis” American J of Pharmacy 140: 137 (1968)

Manske, RHF, “Synthesis of the Methyl-Tryptamines and Some Derivatives” Canadian Journal of Research 5: 592-600 (1931)

Szara, SI, “The comparison of the psychotic effects of tryptamine derivatives with the effects of mescaline and LSD-25 in self experiments.” In Psychotropic Drugs, Garraitini & Ghetti Editors, New York Elsevier pg 460-467 (1957)

Pinkley, HV “Plant Admixtures to Auahuasca, the South American Hallucinogenic Drink.” Lloydia 32: 305ff (1969)

McKenna, D, Towers, GHN, Abbott, FS, “Monoamine oxidase Inhibitors in South American Hallucinogenic Plants: Tryptamine and Beta Carboline constituents of Ayahuasca” J of Ethnopharmacology 10: 195-223 (1984)

Luna, LE, “The Healing Practices of a Peruvian Shaman. and The Concept of Plants as Teachers Among Four Mestizo Shamans of Iquitos, Northeast Peru.” J of Ethnopharmacology 11: 123-156 (1984)

McKenna, DJ, Luna, LE, and Towers, GHN, “Biodynamic Constituents in Ayahuasca Admixture Plants: An Uninvestigated Folk Pharmacopoeia” Ethnobotany: Evolution of a Discipline, ed. Von Reis, S, Schultes, RE Portland: Dioscorides Press (1995)

Callaway, JC, Airaksinen, MM, McKenna, DJ, Brito, GS, Grob, CS; “Platelet Serotonin Uptake Sites Increased in Drinkers of Ayahuasca.” Psychopharmacology 116; 385- 387 (1994)

Callaway, JC, Raymon, LP, Hearn, WL, McKenna, DJ, Grob, CS, Brito, GS, Mash, DC; “Quantitation of N,N-dimethyltryptamine and harmala alkaloids in human plasma after oral dosing with Ayahuasca.” J of Analytical Toxicology 20: 492-497 (1996)

McKenna, DJ, Grob, CS, Callaway, JC; “The Scientific Investigation of Ayahuasca: A Review of past and current research.” Hefter Review of Psychedelic research 1: 65-77 (1998)

Callaway, JC, McKenna, DJ, Grob, CS, Brito, GS, Raymon, LP, Poland, RE, Andrade, EN, Andrade, EO, and Mash, DC; “Pharmacokinetics of Hoasca alkaloids in healthy humans.” J of Ethnopharmacology 65 (3) : 243-256 (1999)