Antibiotic Treatment and Your Microbiome: Damage Control & Rehab (22 April 2022)

Scott Emerson, MD, ABIHM, FACMT

Timelesshealing

Antibiotics: A Double Edged Sword (1,2,).

There is no question that ever since penicillin was discovered by Alexander Fleming in 1928, that antibiotics have been used to save countless lives combating infectious diseases. In fact, most persons reading this have experienced the power of thoughtful and responsible use of physician prescribed antibiotics in the past to rescue them from serious infections and even death. But as time has passed over the last 9 decades, thoughtless, irresponsible, misuse and overuse of antibiotics has led to the selection and emergence of widespread antibiotic resistance by many pathogenic bacteria. Reasons for the antibiotic resistance crisis does include some over-prescription by physicians, but most importantly has resulted from widespread additions of antibiotics to the food of animals being used for factory farm meat production. This now poses a global threat to modern medicine’s achievements and is a growing public health problem.

Initially, before growing awareness of our gut microbiome’s central importance as a vitality organ in the body, antibiotics were thought to be only beneficial for patients with very little downside risk. But multiple recent studies over the past decade have illuminated the adverse impact on the friendly bacteria of our gut microbiome from even thoughtful, appropriately targeted use of antibiotics. Our normal gut microbiome contains an average of 40 to 50 trillion bacteria and is very complex with a diversity of at least 1000 different species. These microbes are always producing a vast array of very beneficial biochemical products that we cannot produce on our own. The microbiome is the control panel operator for our immune system, setting the balance of inflammatory and anti-inflammatory states, and the set points of immune surveillance in our bodies. Use of common antibiotics like erythromycin, cephalosporins, or tetracycline leads to rapid development of gut dysbiosis with the normal diversity of the gut microbiome markedly reduced and commonly resulting in antibiotic associated diarrhea. This opens an ecosystem niche for overgrowth of pathogenic gut bacteria like Clostridium difficile and development of increasingly common and severe C. diff Disease. Long-term effects of antibiotics include creation of a leaky gut, immune imbalance, chronic inflammation, and a long list of subsequent disease states. Although there is some ability of the gut microbiome to rebalance itself after a brief course of antibiotics, prolonged use or repeated courses greatly increase the likelihood of a permanent dysbiosis.

SCROLL DOWN TO LAST SECTION FOR ACTIONS TO TAKE FOR DAMAGE CONTROL & REHAB OF YOUR MICROBIOME

Documented Effects of Antibiotics on Friendly Bacteria

Erythromycin & Tetracycline (3).

These commonly used antibiotics are considered bacteriostatic, not bactericidal, meaning that they inhibit bacterial growth but have not been thought to outright kill large numbers of bacteria. But, a recent study by Maier et.al. documented that even a brief treatment with either of these antibiotics led to a rapid, near total killing of several normally abundant friendly gut microbes ( Bacteroides sp.). Of note, pathogenic Clostridia difficile was resistant to all the erythromycin class of antibiotics, and was not affected.

Broad Spectrum Antibiotics (4, 5).

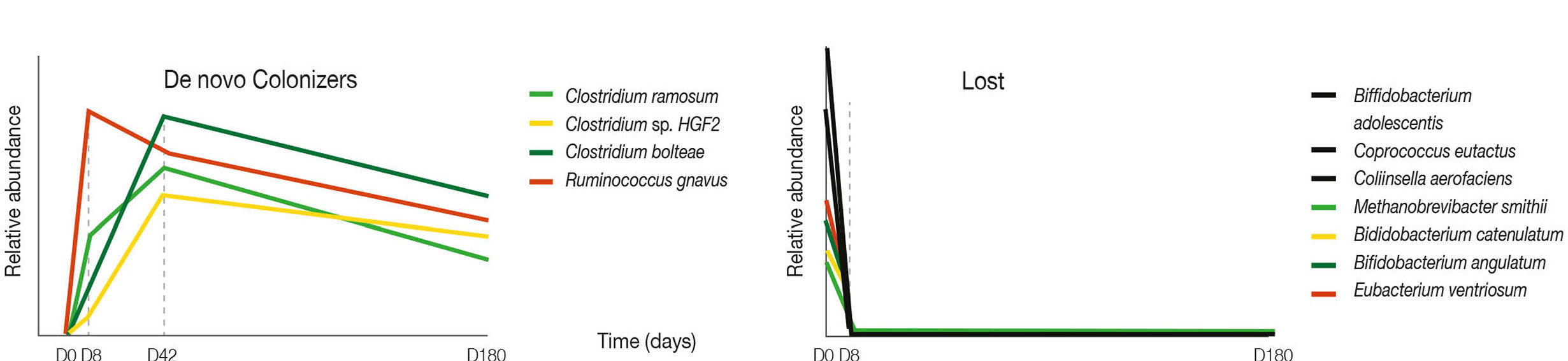

A recent report by Ramirez et. al. showed that a 4 day treatment with meropenem, gentamycin and vancomycin resulted in permanent loss, at 180 days post treatment, of multiple friendly butyrate producing Bifidobacterium sp.. This same study showed that pathogenic opportunists like Klebsiella sp. and new colonizers like Clostridia sp. had increased their relative abundance at 180 days post treatment. In addition, standard doses of cephalosporins ( ex. ceftriaxone), carbapenems ( ex. imipenem) and fluoroquinolones (ex. moxifloxacin) have been shown to eliminate or greatly decrease friendly Bifidobacterium sp.

DAYS 1- 180 ON HORIZONTAL AXIS; RELATIVE ABUNDANCE OF BACTERIAL SPECIES ON VERTICAL AXIS. ANTIBIOTICS WERE GIVEN ONLY DAYS 1-4, THEN STOPPED. NOTE THAT MANY BENEFICIAL BACTERIAL SPECIES APPEAR TO BE QUICKLY & PERMANENTLY LOST, OUT AT LEAST FOR 180 DAYS AFTER JUST 4 DAYS OF ANTIBIOTICS (RIGHT), WHILE NEW & DIFFERENT COLONIZER BACTERIA ROSE SHARPLY VERY QUICKLY TO FILL THIS VACANT ECOLOGICAL NICHE. (LEFT) (Ramirez, et.al. 2020)

“Non-Antibiotic” Antibiotics (6).

Chemotherapy, radiation therapy and immunotherapy used for cancer treatment are well documented to decrease the diversity of the gut microbiome and specifically decrease beneficial butyrate producing microbes such as Faecalibacterium, Rosburia, & Coprococcus. In parallel, pathogenic, pro-inflammatory bacteria numbers increase. These destructive changes in the microbiome are greatly amplified by use of traditional antibiotics in cancer patients with adverse effects on cancer immune surveillance. Use of a course of traditional antibiotics in patients in remission from leukemia is now being observed as a possible trigger for the relapse of cancer.

Microbiome Antibiotic Damage Control.

We will all probably need to take a course of antibiotics from time to time. So how can we protect our microbiome organ from collateral damage when we take them?

Dicumarol (3,7).

YELLOW FLOWERING SWEET CLOVER CONTAINS AN ENTOURAGE OF COUMARINS, INCLUDING DICUMAROL

This compound is found naturally in Melitotus officinalis (yellow flowering sweet clover tea) as well as cassia cinnamon. It has recently been shown that it protects beneficial gut Bacteroides sp. from collateral damage caused by erythromycin and tetracycline types of antibiotics. Notably, this compound did not affect antibiotic efficacy against the pathogens for which these antibiotics were prescribed. It may also have microbiome sparing effects for other antibiotics as well, but this remains to be studied. Dicumarol is also a blood thinning medicine, but is probably very safe when consumed from natural products and spices (above). However, all those on any blood thinner meds should avoid even these natural sources.

This compound is found naturally in Melitotus officinalis (yellow flowering sweet clover tea) as well as cassia cinnamon. It has recently been shown that it protects beneficial gut Bacteroides sp. from collateral damage caused by erythromycin and tetracycline types of antibiotics. Notably, this compound did not affect antibiotic efficacy against the pathogens for which these antibiotics were prescribed. It may also have microbiome sparing effects for other antibiotics as well, but this remains to be studied. Dicumarol is also a blood thinning medicine, but is probably very safe when consumed from natural products and spices (above). However, all those on any blood thinner meds should avoid even these natural sources.

Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745 strain – Florastor Brand ( 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 ).

This strain of wild tropical yeast was discovered in Indochina 100 years ago by French mycologist Henri Boulard when he observed indigenous shamans using teas of the boiled skins of lychee and mangosteen fruits to successfully treat cholera. It is resistant to heat, gastric acid, and bacterial antibiotics. The use of this yeast probiotic during the course of traditional antibiotic treatment has been documented to significantly reduce the incidence of antibiotic associated diarrhea, development of antibiotic associated C. diff disease, and relapse of recurrent C. diff disease.

In addition, S. boulardii has been used effectively to significantly reduce the antibiotic side effects from the triple therapy used to treat H. pylori infections. It creates effects which resemble the protective nature of the normal healthy gut flora while you are taking antibiotics. There are some isolated case reports of S. boulardi supplementation that have spread into the blood stream. These all occurred in either immunocompromised patients, or from inadvertent contamination of a patient’s central venous catheter. All were successfully treated. No adverse effects have been observed in any of the clinical trials. It is very safe. S.boulardi does not colonize the intestine and is completely eliminated within 3 days of stopping the probiotic supplement. The mechanisms of the S. boulardii GI protection are complex and include effects like producing bacterial toxin neutralizing compounds, and causing pathogenic bacteria to irreversibly adhere to its surface. This draws the pathogens away from attacking the intestinal epithelium and eliminates them in the stool. It produces short chain fatty acids providing an energy source to the gut epithelial cells as well as support for friendly bacteria.

Fermented Foods

Fermented Foods like kimchi, sauerkraut, and tempeh uniquely offer: soluble fiber – a prebiotic food for beneficial bacteria, live Lactobacillus sp. bacteria – a beneficial probiotic, and, lots of bacterial created short chain fatty acids – postbiotics that support beneficial bacteria and your intestinal cells.

Probiotics

Probiotics are live microorganisms that when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host. Yes, bacterial probiotics will likely be killed if taken at the same time as an antibacterial antibiotic. But, if taken several hours after the antibiotic pill, they will likely survive a safe passage to the large intestine where biofilm formation may protect them. This may serve as reinforcements for beneficial bacteria taken out by the antibiotic.

Steps Adults Can Take to Control Collateral Damage to Your Gut Microbiome While Taking a Course of Antibiotics & to Rehab Your Microbiome Afterward.

1. Drink Yellow Sweet Clover Tea and, or, use ground Cassia Cinnamon as a spice topping on daily breakfast oatmeal – a prebiotic food.

2. Eat Extra Amounts of Fermented Foods (kimchi, sauerkraut, tempeh etc..) while taking your antibiotic.

3. Take 2 capsules of a quality probiotic with good independent reviews, and with a minimum of 16 different bacterial strains and at least 50 billion colony forming units (CFU) per capsule (total of at least 100 billion CFU) at least once a day. This dose should be timed several hours away from the antibiotic dose. Continue this dose all the while you are on antibiotics and for 4 weeks after the antibiotic course is complete, then stop. (Suggested brands to look for: Activated You, or, Stone Henge Health probiotics).

4. Take Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745 strain (Florastor Brand) yeast probiotic at least 10 billion CFUs a day (500 mg. capsules – up to maximum of 4 per day, 1 to 2 capsules 1 to 2 times a day) while on your antibiotic course, then discontinue once your antibiotic course is completed.

5. Regular Exercise (17). And last but not least, brisk walking or hiking an hour a day with an occasional more intense work-out has been shown to correct imbalances and increase the diversity in your gut microbiota very quickly. Ask your physician that prescribed the antibiotic if its OK to begin or continue moderate daily exercise (brisk walking) while on your antibiotic course and , or, after completion.

*Note: If immunocompromised or have an indwelling central IV catheter, it is advised that you follow only steps 1 thru 3 above. And consider adding the postbiotic, “Tributyrin” instead, during the antibiotic course.

If on blood thinners of any type, follow only steps 2 thru 4 above.

I have no financial interest in any of the specific products mentioned above.

References.

- Konstantinidis, T. et. al., “Effects of Antibiotics upon the Gut Microbiome: A Review of the Literature” Biomedicines 8: 502; doi: 10.3390 (2020)

- Rinninella, E et al “What is the Healthy Gut Microbiota Composition? A Changing Ecosystem across Age, Environment, Deit and Diseases” Microorganisms. 7: 14 1-22 (2019)

- Maier, L. “Unraveling the collateral damage of antibiotics on gut bacteria” Nature Vol 599 120-124 (November 2021)

- Ramirez, J. “Antibiotics as Major Disrupters of Gut Microbiota” Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 10: 572912. (2020)

- Accelerate Diagnostics, Inc. Scientific Affairs, Tucson, AZ, J Antimicrob Chemother 74: Suppl 1: 6-15 (2019)

- Pagani, H., “Review: A Gut Instinct on Leukaemia: A New Mechanistic Hypothesis for Microbiota-Immune Crosstalk in Disease Progression and Relapse” Microorganisms 10: 713 pg 1-14 (2022)

- Loncar, M. “Coumarins in Food and Methods of their Determination” Foods 9: 644-676 (2020)

- Kelesidis, T. Et. al. “Efficacy and Safety of the Probiotic Saccharomyces boulardii for the Prevntion and Therapy of Gastrointestinal Disorders” Theraputic Advances in Gastroenterology (5(2) 111-125 (2012)

- Scheike, I. et. al. “Probiotics for the Prevention of Antibiotic Associated Diarrhea”: A Systematic Review” Dept of Health and Epidemiology, The Univ . of Birmingham Report #56 (2006)

- McFarland, L. “Meta-analysis of Probiotics for the Prevention of Antibiotic Associated Diarrhea & Treatment of C. diff Disease” Am J. of Gastroenterol 101: 812-822 (2006)

- McFarland, L. et.al. “A Randomized placebo controlled trial of S. boulardii in combination with standard antibiotics for C.diff disease” JAMA 271: 1913-1918 (1994)

- Surawicz, C. et.al. “Prevention of antibiotic Associated Diarrhea by S. boulardii: A Prospective Study” Gastroenterology 96 : 981-988 (1989)

- McFarland, L. et.al. “Prvention of Beta Lactam Associated diarrhea by S. boulardii compared with placebo” Am J. Gastroenterology 90: 439-448 (1995)

- Can, M. et. al. “Prophylactic S boulardi in the Prevention of Antibiotic Associated diarrhea : A Prospective Study” Med Sci Monit 12 : 119-122 (2006)

- Surawicz, C. et.al. “The Search for Better Treatment for Recurrent C. diff Disease: Use of high dose Vancomycin combined with S. boulardii” Clin Inf Dis 31: 1012-1017 (2000)

- Pais, P. et.al. “Saccharomyces boulardii: What Makes it Tick as Successful Probiotic?” Journal of fungi 6: 78 (2020)

- Ohad, M et al “Health & Disease Markers Correlate with Gut Microbiome Composition Across Thousands of People” Nature Communications doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18871-1 1- 12 (2020)